Division of Social Studies News by Date

Results 1-7 of 7

March 2021

03-29-2021

The OSUN Center for Human Rights and the Arts at Bard College has announced the launch of a pioneering master of arts program in human rights and the arts, and looks forward to welcoming the inaugural class in fall 2021. Designed by the Center’s core faculty team of Tania El Khoury, Thomas Keenan, Gideon Lester, and Ziad Abu-Rish, the interdisciplinary program will bring together scholars, artists, and activists from around the world to explore the productive and contentious relation between the arts and struggles for truth and justice. The program expands the curricular and extracurricular elements of the OSUN Center, directed by El Khoury.

The Center has set a May 1 priority application deadline and a June 15 final deadline. Ample need-based financial aid is available to cover tuition and other expenses. The following information sessions will be open to the public and prospective applicants (please register by emailing [email protected] with full name and intended session to receive a Zoom link).

The Center has set a May 1 priority application deadline and a June 15 final deadline. Ample need-based financial aid is available to cover tuition and other expenses. The following information sessions will be open to the public and prospective applicants (please register by emailing [email protected] with full name and intended session to receive a Zoom link).

- Tuesday, April 6, at 8:30am NYC Time (2:30pm Vienna / 6:30pm Dhaka)

- Wednesday, April 7, at 4:00pm NYC Time (10pm Vienna / 2:00am Dhaka)

- Monday, April 12, at 8:00am NYC Time (2:00pm Vienna / 6:00pm Dhaka)

- Friday, April 15, at 4:00pm NYC Time (10pm Vienna / 2:00am Dhaka)

Photo: Photo by Maria Baranova

Meta: Subject(s): Bard Graduate Programs,Division of Social Studies,Division of the Arts,Human Rights | Institutes(s): Center for Human Rights and Arts (CHRA) |

Meta: Subject(s): Bard Graduate Programs,Division of Social Studies,Division of the Arts,Human Rights | Institutes(s): Center for Human Rights and Arts (CHRA) |

03-29-2021

Ahead of elections in the northeastern Indian state of Assam, Scroll.in spoke with Sanjib Baruah, professor of political studies at Bard College and author of In the Name of the Nation: India and Its Northeast. Baruah discussed how the past animates Assam’s present and what new political imaginations can help unshackle these memory-driven regimes of belongingness for a more inclusive future.

Photo: Professor Sanjib Baruah. Photo by Pete Mauney ’93 MFA ’00

Meta: Type(s): Faculty | Subject(s): Division of Social Studies,Political Studies Program | Institutes(s): Bard Undergraduate Programs |

Meta: Type(s): Faculty | Subject(s): Division of Social Studies,Political Studies Program | Institutes(s): Bard Undergraduate Programs |

03-19-2021

The Bard Globalization and International Affairs Program profiles Jahari Fraser, a Bard junior and Posse Scholar studying Global and International Studies and Spanish Studies. This semester, Jahari is studying at BGIA and interning at Project CETI, a nonprofit organization and 2020 TED Audacious Project Grant recipient that is applying advanced machine learning and non-invasive robotics to listen to and translate the communication of whales. Some of Jahari’s work will be aimed toward Project CETI’s launch in mid-April, including various research projects and contributing to CETI’s overall organizational development.

Photo: Jahari Fraser ’22.

Meta: Type(s): Student | Subject(s): Division of Languages and Literature,Division of Social Studies,Foreign Languages, Cultures, and Literatures Program,Global and International Studies | Institutes(s): Bard Undergraduate Programs,Posse Foundation |

Meta: Type(s): Student | Subject(s): Division of Languages and Literature,Division of Social Studies,Foreign Languages, Cultures, and Literatures Program,Global and International Studies | Institutes(s): Bard Undergraduate Programs,Posse Foundation |

03-19-2021

“There are, of course, many criticisms that should be levelled at Churchill’s wartime policies,” writes Sean McMeekin, Francis Flournoy Professor of European History and Culture. “But there is one in particular that, in the rush to paint him as a racist imperialist, has avoided scrutiny: his relationship with Stalin. Churchill, in fact, sacrificed British imperial interests in order to save Soviet communism. Stalin could not have asked for a friendlier British government.”

Photo: Getty Images.

Meta: Type(s): Faculty | Subject(s): Division of Social Studies,Historical Studies Program,Russian and Eurasian Studies Program | Institutes(s): Bard Undergraduate Programs |

Meta: Type(s): Faculty | Subject(s): Division of Social Studies,Historical Studies Program,Russian and Eurasian Studies Program | Institutes(s): Bard Undergraduate Programs |

03-17-2021

By Myra Young Armstead

Vice President for Academic Inclusive Excellence and Lyford Paterson Edwards and Helen Gray Edwards Professor of Historical Studies

We can find clues to the past in the built environment—as examples: a cul de sac, a plaza, a park, a neighborhood of turreted houses, the clustering of certain shops, monuments, and, importantly, the unnoticed, naturalized, familiar names of streets and buildings. These artifacts, constructions, and materialized symbols literally map who and what we value as members of society. This is true on the local level, too. McKenzie House on the south end of Bard’s campus just past the triangle on Annandale Road is so named in honor of Emerald Rose McKenzie ’52, one of the first African American women to graduate from the College. She majored in sociology as an undergraduate here and went on to a long, successful career as a social worker for the Jewish Guild for the Blind after receiving a master’s degree in that field from New York University. McKenzie’s singular presence at Bard in the 1950s prompts interrogations into the intersectionalities of her identity as a woman, a Black person, and a disabled/visually handicapped person in the immediate postwar period. What follows is just a start.

Emerald was born in Nassau, the Bahamas, on September 17, 1927, and shortly thereafter emigrated to the United States with her parents and siblings. By 1930, her working-class family lived in Brooklyn in a quadruplex building erected on Sutter Avenue in 1901 near the border of Brownsville and East New York. Her father worked as a clerk that year for a meatpacking company, supporting his wife and their four children, of which Emerald was the youngest at just two years of age. When he passed two years later, his death certificate listed him as a tailor. In some ways, the family’s circumstances seem to have improved since they were now living on Warwick Street—still in Brownsville but in a newer multifamily building constructed in 1930. In the 1930s, Brownsville was still a predominantly Russian Jewish area of Brooklyn, with a recent influx of Southern Black migrants and Caribbean immigrants representing roughly 6 percent of the total population by 1940. In that year, Emerald’s widowed mother, Alma, headed a household that consisted of the same four siblings as before with a younger nine-year-old brother now added to the mix. The Black population grew during Emerald’s childhood, so that by 1950 it had doubled and was concentrated in Brownsville’s least desirable housing. However, the New Deal’s National Youth Administration employment program allowed Emerald’s older sister Hermine to add to the family income as a teacher’s secretary in 1940. Another older sister, Dorit, worked as an “operator” in a dressmaking factory that same year. She probably was a sewing machine operator. Cynthia Dantzic, whose undergraduate years at Bard partially overlapped with Emerald’s, recalls that Hermine was a fine, highly skilled seamstress, too. Before the 1950s, the family moved to a private house with a large rear garden on Bainbridge Street, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn. This neighborhood in central Brooklyn, known for its beautiful brownstones, drew “large numbers of eastern European Jews, Italians, and later blacks from the South and the Caribbean” in the 1930s, although by Emerald’s teen years in the 1940s the area was becoming predominantly Black as others moved out.

Cynthia explained that Emerald was born with some visual impairment but that some later physical trauma, perhaps an athletic accident , left her completely sightless when she was 16. That would have been in 1948. However, the accident must have occurred earlier because according to Bard College admissions records, Emerald attended the New York Institute for the Education of the Blind (NYIEB) for four years and graduated in 1948. (In 1986 the NYIEB was renamed the New York Institute for Special Education, serving “children with visual impairments but also children with emotional/learning needs and preschool children with developmental disabilities.”)

Education was clearly a priority Emerald held for herself with the full support of her family. In the 1940s, there were two high schools for blind students in New York City—the NYIEB on Pelham Parkway in the Bronx, and the Lavelle School for the Blind on Paulding Avenue in the Bronx; the latter was Catholic but recognized in 1942 by the New York State Education Department, from which it began receiving funding. Both options for Emerald Rose required either a long daily commute from Brooklyn to the Bronx—a daunting undertaking for a sighted student, so much more so for a blind one—or residential status at the school. It is almost certain that Emerald Rose lived on the campus of the NYIEB from 1944 until her graduation in 1948.

McKenzie came to Bard College as a transfer student, having spent her first undergraduate year at Brooklyn College. In the fall of 1949 when she matriculated in Annandale as a sophomore, Brooklyn College was just 13 years old—a progressive educational project of the New Deal era designed as the country’s first coeducational, public liberal arts college and as “a stepping stone for the sons and daughters of immigrants and working-class people toward a better life through a superb—and at the time, free—college education.” The school was in Brooklyn, her home, and free, but one can only imagine the physical challenges she faced as a blind student at a large, urban school built for persons with full visual abilities.

Somehow, McKenzie learned about Bard. Like Brooklyn College, the College had recently (in 1944) become coeducational, and through a generous scholarship from the American Federation for the Blind her educational costs were completely covered. The coeducational aspect of Bard was a huge draw. In the fall of 1949, 121 women joined 149 men to make up the total student population. By way of contrast, Dantzic recalled that when she, another Brooklynite, graduated high school, she hoped to study art at Yale but was discouraged to learn that the Ivy did not accept women as undergraduates who were coming straight out of high school. (For that reason, Dantzic spent her first two college years at Bard with the intention of transferring to Yale, which she did for her B.F.A.) A second draw for McKenzie was the small size of the College (only 270 students when she entered), the quiet pace of things, and the individualized attention she could receive from her professors. Dantzic recalled the bucolic setting, McKenzie’s well-trained seeing-eye dog, Karen, and the kind of basic academic resources available to Emerald Rose—books in Braille; audiobooks on discs; a paid, personalized course book reader (Dantzic performed this service for McKenzie); and a Braille typewriter.

With this initial article, the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion is launching a longer historical project on Emerald Rose McKenzie, the state of higher education for the visually impaired nationally during her lifetime, where Bard stood in relation to national standards then, and where it stands now. We are still researching more precise details of McKenzie’s biography and invite students interested in participating in this project to contact me, Myra Armstead, at [email protected]. In conjunction with the Archives Working Group of the Council for Inclusive Excellence, we are also beginning to research the longer history of disability awareness at Bard and are pleased to have the cooperation of Finn Tait ’22 as president and founder of the Bard Disabled Students Union.

NOTES

1. U.S. Census, 1930; U.S. Census, 1940; Wendell Pritchett, Brownsville, Brooklyn: Blacks, Jews, and the Changing Face of the Ghetto (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 84.

2. Cynthia Dantzic, Interview with Myra Young Armstead, March 8, 2021.

3. “A Brief History of NYISE,” nyise.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=391515&type=d&pREC_ID=922947, accessed March 15, 2021.

4. “Brooklyn College: Our History,” brooklyn.cuny.edu/web/about/history/ourhistory.php, accessed March 15, 2021.

Vice President for Academic Inclusive Excellence and Lyford Paterson Edwards and Helen Gray Edwards Professor of Historical Studies

We can find clues to the past in the built environment—as examples: a cul de sac, a plaza, a park, a neighborhood of turreted houses, the clustering of certain shops, monuments, and, importantly, the unnoticed, naturalized, familiar names of streets and buildings. These artifacts, constructions, and materialized symbols literally map who and what we value as members of society. This is true on the local level, too. McKenzie House on the south end of Bard’s campus just past the triangle on Annandale Road is so named in honor of Emerald Rose McKenzie ’52, one of the first African American women to graduate from the College. She majored in sociology as an undergraduate here and went on to a long, successful career as a social worker for the Jewish Guild for the Blind after receiving a master’s degree in that field from New York University. McKenzie’s singular presence at Bard in the 1950s prompts interrogations into the intersectionalities of her identity as a woman, a Black person, and a disabled/visually handicapped person in the immediate postwar period. What follows is just a start.

Emerald was born in Nassau, the Bahamas, on September 17, 1927, and shortly thereafter emigrated to the United States with her parents and siblings. By 1930, her working-class family lived in Brooklyn in a quadruplex building erected on Sutter Avenue in 1901 near the border of Brownsville and East New York. Her father worked as a clerk that year for a meatpacking company, supporting his wife and their four children, of which Emerald was the youngest at just two years of age. When he passed two years later, his death certificate listed him as a tailor. In some ways, the family’s circumstances seem to have improved since they were now living on Warwick Street—still in Brownsville but in a newer multifamily building constructed in 1930. In the 1930s, Brownsville was still a predominantly Russian Jewish area of Brooklyn, with a recent influx of Southern Black migrants and Caribbean immigrants representing roughly 6 percent of the total population by 1940. In that year, Emerald’s widowed mother, Alma, headed a household that consisted of the same four siblings as before with a younger nine-year-old brother now added to the mix. The Black population grew during Emerald’s childhood, so that by 1950 it had doubled and was concentrated in Brownsville’s least desirable housing. However, the New Deal’s National Youth Administration employment program allowed Emerald’s older sister Hermine to add to the family income as a teacher’s secretary in 1940. Another older sister, Dorit, worked as an “operator” in a dressmaking factory that same year. She probably was a sewing machine operator. Cynthia Dantzic, whose undergraduate years at Bard partially overlapped with Emerald’s, recalls that Hermine was a fine, highly skilled seamstress, too. Before the 1950s, the family moved to a private house with a large rear garden on Bainbridge Street, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn. This neighborhood in central Brooklyn, known for its beautiful brownstones, drew “large numbers of eastern European Jews, Italians, and later blacks from the South and the Caribbean” in the 1930s, although by Emerald’s teen years in the 1940s the area was becoming predominantly Black as others moved out.

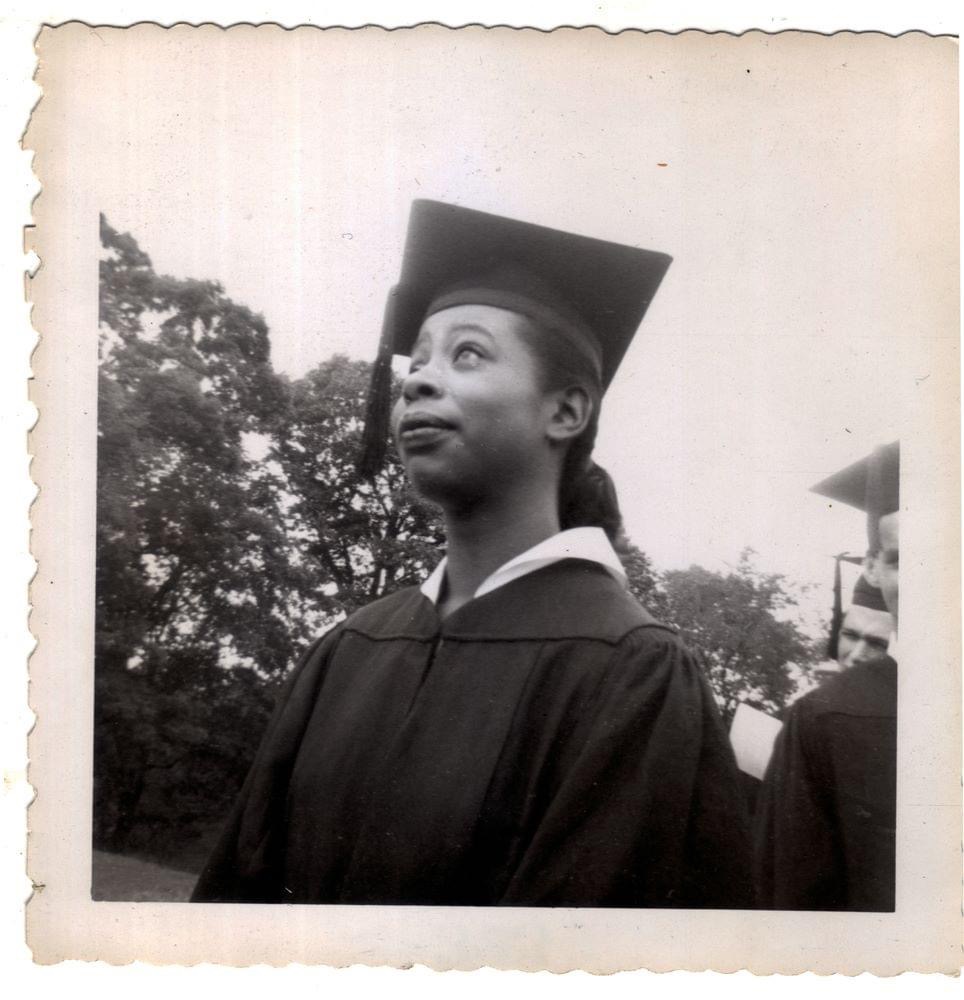

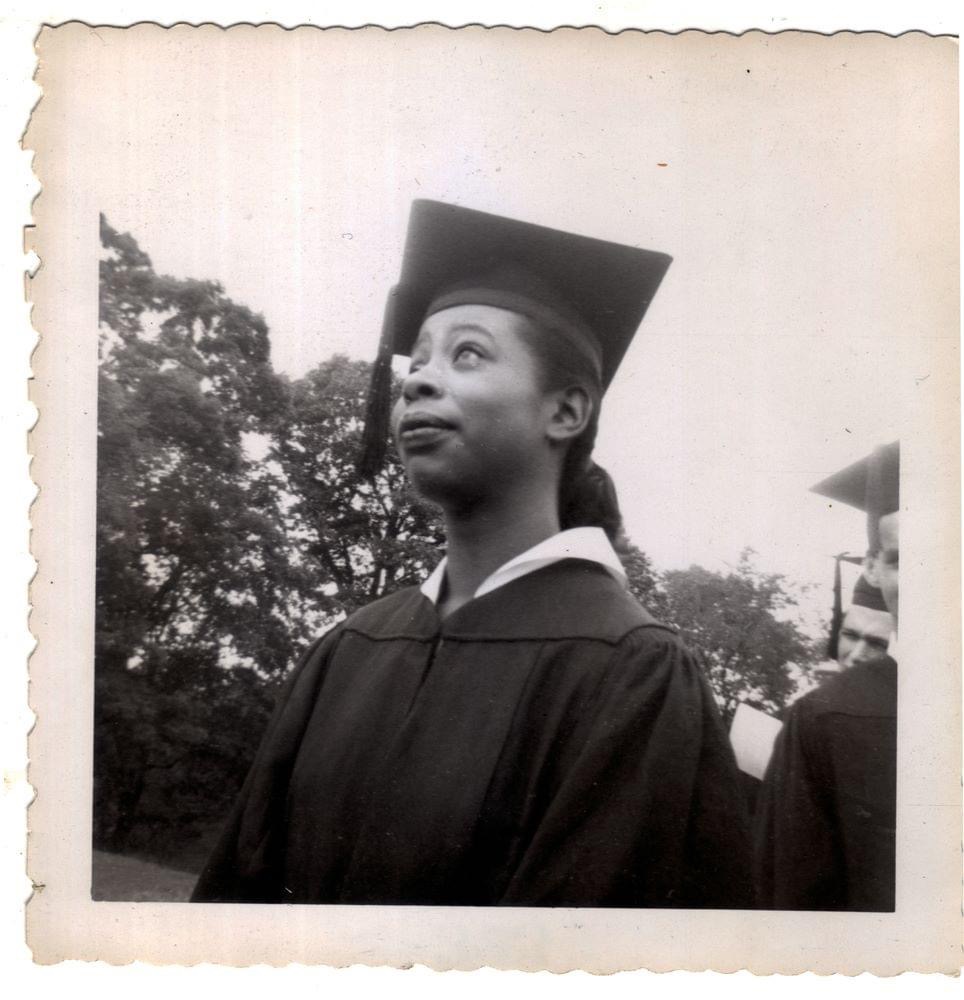

Emerald Rose McKenzie ’52 at Bard College Commencement. Courtesy Cynthia Dantzic

Cynthia explained that Emerald was born with some visual impairment but that some later physical trauma, perhaps an athletic accident , left her completely sightless when she was 16. That would have been in 1948. However, the accident must have occurred earlier because according to Bard College admissions records, Emerald attended the New York Institute for the Education of the Blind (NYIEB) for four years and graduated in 1948. (In 1986 the NYIEB was renamed the New York Institute for Special Education, serving “children with visual impairments but also children with emotional/learning needs and preschool children with developmental disabilities.”)

Education was clearly a priority Emerald held for herself with the full support of her family. In the 1940s, there were two high schools for blind students in New York City—the NYIEB on Pelham Parkway in the Bronx, and the Lavelle School for the Blind on Paulding Avenue in the Bronx; the latter was Catholic but recognized in 1942 by the New York State Education Department, from which it began receiving funding. Both options for Emerald Rose required either a long daily commute from Brooklyn to the Bronx—a daunting undertaking for a sighted student, so much more so for a blind one—or residential status at the school. It is almost certain that Emerald Rose lived on the campus of the NYIEB from 1944 until her graduation in 1948.

Cynthia Maris Gross ’54 reads to Emerald McKenzie ’52, 1952. McKenzie is seen here with her seeing-eye dog, Karen. Gross acted as McKenzie’s “reader” throughout their shared time at Bard. Photograph by David Brook.

McKenzie came to Bard College as a transfer student, having spent her first undergraduate year at Brooklyn College. In the fall of 1949 when she matriculated in Annandale as a sophomore, Brooklyn College was just 13 years old—a progressive educational project of the New Deal era designed as the country’s first coeducational, public liberal arts college and as “a stepping stone for the sons and daughters of immigrants and working-class people toward a better life through a superb—and at the time, free—college education.” The school was in Brooklyn, her home, and free, but one can only imagine the physical challenges she faced as a blind student at a large, urban school built for persons with full visual abilities.

Somehow, McKenzie learned about Bard. Like Brooklyn College, the College had recently (in 1944) become coeducational, and through a generous scholarship from the American Federation for the Blind her educational costs were completely covered. The coeducational aspect of Bard was a huge draw. In the fall of 1949, 121 women joined 149 men to make up the total student population. By way of contrast, Dantzic recalled that when she, another Brooklynite, graduated high school, she hoped to study art at Yale but was discouraged to learn that the Ivy did not accept women as undergraduates who were coming straight out of high school. (For that reason, Dantzic spent her first two college years at Bard with the intention of transferring to Yale, which she did for her B.F.A.) A second draw for McKenzie was the small size of the College (only 270 students when she entered), the quiet pace of things, and the individualized attention she could receive from her professors. Dantzic recalled the bucolic setting, McKenzie’s well-trained seeing-eye dog, Karen, and the kind of basic academic resources available to Emerald Rose—books in Braille; audiobooks on discs; a paid, personalized course book reader (Dantzic performed this service for McKenzie); and a Braille typewriter.

With this initial article, the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion is launching a longer historical project on Emerald Rose McKenzie, the state of higher education for the visually impaired nationally during her lifetime, where Bard stood in relation to national standards then, and where it stands now. We are still researching more precise details of McKenzie’s biography and invite students interested in participating in this project to contact me, Myra Armstead, at [email protected]. In conjunction with the Archives Working Group of the Council for Inclusive Excellence, we are also beginning to research the longer history of disability awareness at Bard and are pleased to have the cooperation of Finn Tait ’22 as president and founder of the Bard Disabled Students Union.

NOTES

1. U.S. Census, 1930; U.S. Census, 1940; Wendell Pritchett, Brownsville, Brooklyn: Blacks, Jews, and the Changing Face of the Ghetto (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 84.

2. Cynthia Dantzic, Interview with Myra Young Armstead, March 8, 2021.

3. “A Brief History of NYISE,” nyise.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=391515&type=d&pREC_ID=922947, accessed March 15, 2021.

4. “Brooklyn College: Our History,” brooklyn.cuny.edu/web/about/history/ourhistory.php, accessed March 15, 2021.

Photo: Emerald Rose McKenzie ’52. Courtesy Cynthia Dantzic

Meta: Type(s): Alumni | Subject(s): American and Indigenous Studies Program,Division of Social Studies,Gender and Sexuality Studies,Historical Studies Program,Inclusive Excellence |

Meta: Type(s): Alumni | Subject(s): American and Indigenous Studies Program,Division of Social Studies,Gender and Sexuality Studies,Historical Studies Program,Inclusive Excellence |

03-03-2021

“How can we possibly hope to address mass unemployment without economic growth? Fortunately, there’s a straightforward solution. We can fix the problem directly without needing additional growth by introducing a progressive, public job guarantee program, as proposed by economists like Stephanie Kelton, Pavlina Tcherneva, and a growing chorus of others,” writes Jason Hickel. “The idea is that anyone who signs up can train to do dignified, socially useful work (the opposite of ‘bullshit jobs’) and be paid at a living wage.”

Photo: Wind power generators are enveloped in a smoky sky near the Millard fire near Cabazon, California, on July 15, 2006. David McNew/Getty Images, courtesy Foreign Policy

Meta: Type(s): Article,Faculty | Subject(s): Division of Social Studies,Economics,Economics and Finance Program,Economics Program | Institutes(s): Bard Undergraduate Programs |

Meta: Type(s): Article,Faculty | Subject(s): Division of Social Studies,Economics,Economics and Finance Program,Economics Program | Institutes(s): Bard Undergraduate Programs |

03-02-2021

“If skeptics underestimate the effect the climate movement will have on the world’s economy, greens are in danger of overestimating how much their efforts will help the polar bears,” writes Mead, James Clarke Chace Professor of Foreign Affairs and the Humanities at Bard College, in the Wall Street Journal. “Paradoxically, as climate change assumes a more prominent place on the international agenda, climate activists will lose influence over climate policy.”

Photo: Polar bears in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, March 6, 2007. Photo by Reuters

Meta: Type(s): Article,Faculty | Subject(s): Bard Graduate Programs,Division of Social Studies,Environmental/Sustainability,Global and International Studies,Political Studies Program,Politics and International Affairs | Institutes(s): Bard Globalization and International Affairs Program,Bard Undergraduate Programs |

Meta: Type(s): Article,Faculty | Subject(s): Bard Graduate Programs,Division of Social Studies,Environmental/Sustainability,Global and International Studies,Political Studies Program,Politics and International Affairs | Institutes(s): Bard Globalization and International Affairs Program,Bard Undergraduate Programs |

Results 1-7 of 7